The story of the “Lepa Brena phenomenon” is far broader than a repertoire of popular songs; in a sense, it’s almost metaphysical, a saga of Yugoslavia, its rich pop culture, and a socialist society of 22 million ready to embrace camp iconography. To people today, it might seem strange to hear that the former Yugoslavia once had a legally regulated system to protect citizens from “trash culture”—essentially a tax on kitsch. This controversial law, intentionally or otherwise, fostered a unique creative climate where artists flirted with the boundaries of kitsch and art, creating what we now recognize as “YU camp.”

Defining camp is nearly impossible without delving into dry theory—and camp is anything but boring. It’s a counterpoint to overthinking; it’s about how you receive content, not the content itself. Exciting, shocking, exaggerated, loud, and self-ironic, camp is extravagance enjoyed with a certain degree of intimate discomfort. It’s a way of pushing your boundaries, a spice that quickens the sensory metabolism. “Guilty pleasures” are crucial to forming one’s taste and aesthetics. People who consciously deprive themselves of any “kitsch joy” often end up dull and preachy—Saturn’s disciples ready to impose their idea of “good taste” as if it were the eleventh commandment.

Somewhere between the desire to censor and regulate, a unique “YU camp” was born. In 1971, at a Congress for Cultural Action in Kragujevac, an initiative to introduce a “Law on Trash Culture” emerged. The Communist Party of Yugoslavia quickly gathered cultural workers, from Nobel prize-winning author Ivo Andrić to actress Milena Dravić, to discuss the idea of using sales tax laws to support works of “special social and cultural value.” Products that a commission deemed culturally worthless were branded as “trash,” making them up to 50% more expensive. The tax revenue collected this way was channeled into budgets for culture, arts, and education. Cultural workers were satisfied with the arrangement.

In theory, it sounded almost perfect. Initially, this law targeted “pulp” literature—popular romance novels, crime fiction, and comics that dominated kiosks in the early 1970s. We, the “children of communism,” grew up on comic book heroes, blissfully unaware of the extra cost. It was a luxury that built our sense of justice and the belief that good should triumph. Magazines like, Politikin Zabavnik, Stripoteka, and Alan Ford were our initiation into a camp worldview.

By the late 1970s, the biggest challenge—and temptation—for the law’s enforcers was the increasingly powerful music industry of the Yugoslav discography. Editorial censorship by record companies, followed by media censorship, became a strange playing field where terms like “art,” “kitsch,” and “trash” blurred.

The era also coincided with the arrival of “new wave” music. Censors were, to say the least, confused. How do you tax punk? Its subversion left them bewildered, and in a panic, they branded records by bands like Prljavo Kazalište, Lačni Franz, and VIS Idoli with the “trash” label. Even icons of the neo-romantic camp, such as U Škripcu, were labeled trash—not due to provocative lyrics, but for the eroticism of their album O je cover . Thus, poets like Milan Delčić Delča, dark-humored song-writer Zoran Predin, and folk singer Mica Trofrtaljka ended up in the same category as bands such as Pankrti and Bijelo Dugme.

The attempt to shield Yugoslav youth from the thrilling music scene failed spectacularly, and camp was freed from the bottle. This spirit of music, images, visuals, and styles developed and inspired generations, creating a magnificent history of pop culture—an artistic expression worthy of a place in the Museum of Contemporary Art.

While camp worldwide is often linked to the underground club scene, it rarely became mainstream anywhere like it did in the Balkans, then known as Yugoslavia. Whether people like it or not, that spirit remains part of our collective memory and fuels many wonderful phenomena on today’s scene.

BONUS: YU Camp Markers x 10

- Architecture: Across the former Yugoslavia, white buildings with red roofs were designed for workers, embodying the slogan “the right to housing is as natural as saying hello.” These buildings were so “beautiful” that people jokingly called them “Lepa Brena” buildings.

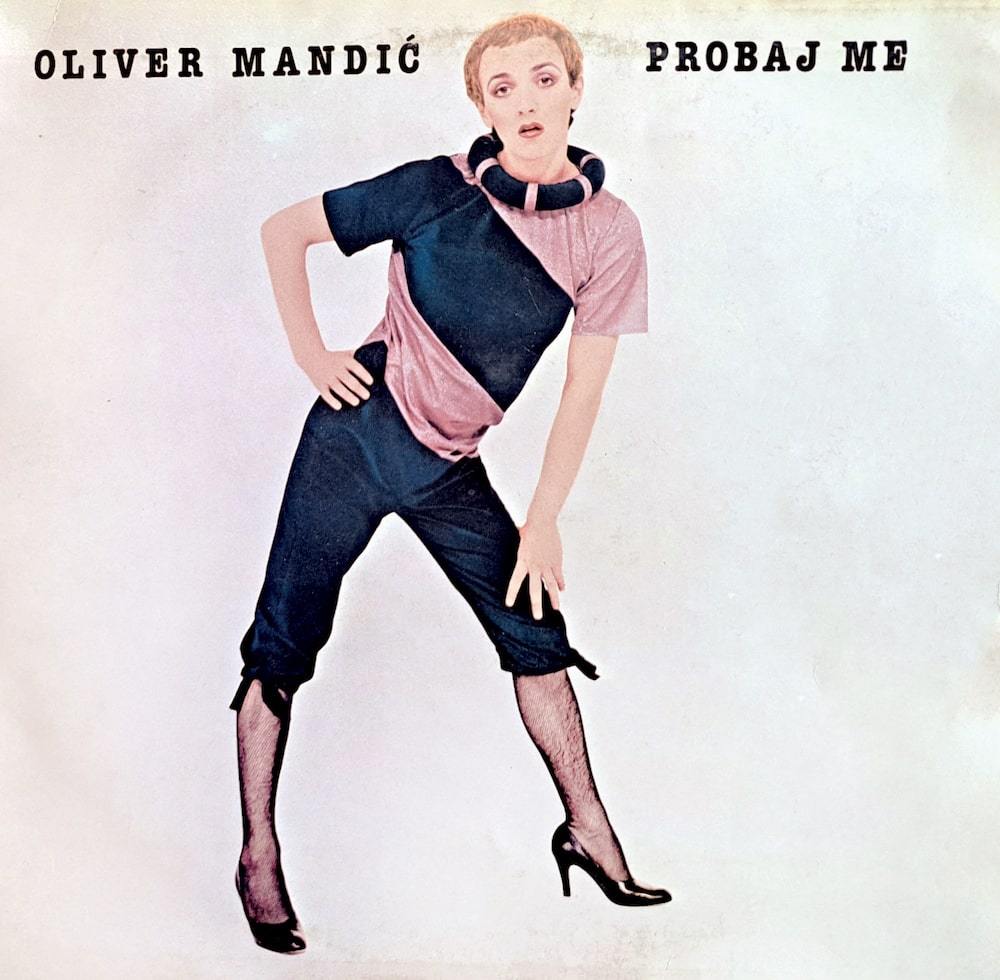

- TV Imagery: The masterpiece Belgrade by Night, where Kosta Bunuševac and Oliver Mandić set a global standard for modern TV expression under the direction of Stanko Crnobrnja.

- Graphic Design: The original cover of Bijelo Dugme’s album Bitanga i princeza showed a gold sandal on a fishnet-covered foot placed provocatively near male groin area, which was deemed vulgar trash and replaced to avoid censorship. Only rare collectors possess the original cover.

- Icon: Singer Bebi Dol’s persona, from the moment she appeared in Alaïa for her single Rudi, declaring that she wore “Aromatic Elixir” and read Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet.

- Music Hit: The subversive anthem Maljčiki was so controversial that the Trash Law essentially protected it from being removed from the airwaves, as was requested by the Soviet Union’s embassy in a formal protest.

- Film Character: Marijana, an iconic character, brought to life by Mira Furlan in Rajko Grlić’s cult classic Štefica Cvek in the Jaws of Life. Marijana’s advice on diet and men, complete with cream cakes, is a masterful “camp” gem of YU cinema.

- Fashion Detail: The disco ball under which singer Slađana Milošević shined during her disco phase. She entered our lives as a sultry bombshell in the late ‘70s, a label she would later fight against. Her music video for Sexy dama is an essential entry on this list.

- Lipstick: The ultimate “camp” lipstick in Yugoslavia was Samantha 17 from Markins collection made by Saponia Osijek company. Even Helena Rubinstein loved it. Today, it’s nearly impossible to recreate, as the pearly shimmer it featured was unique—rumor has it, made with particles from the Ohrid lake pearls.

- Hairstyle: The “Lokica” style, named after Lokica Stefanović’s dance group, was a signature bowl cut styled inward. Everyone across all republics and provinces tried it at least once. Prada recently brought this hairstyle back to the fashion forefront.

- Dance: YU camp wouldn’t be complete without dance. People danced everywhere—on television, at house parties, and in discotheques—as if there were no tomorrow. Singer Marina Perazić was undoubtedly the most imitated dance floor icon. Her routine for the hit song Program tvog kompjutera still shines as a go-to choreography whenever it’s time to dance.

Comments (0)